War and the Woman Engineer

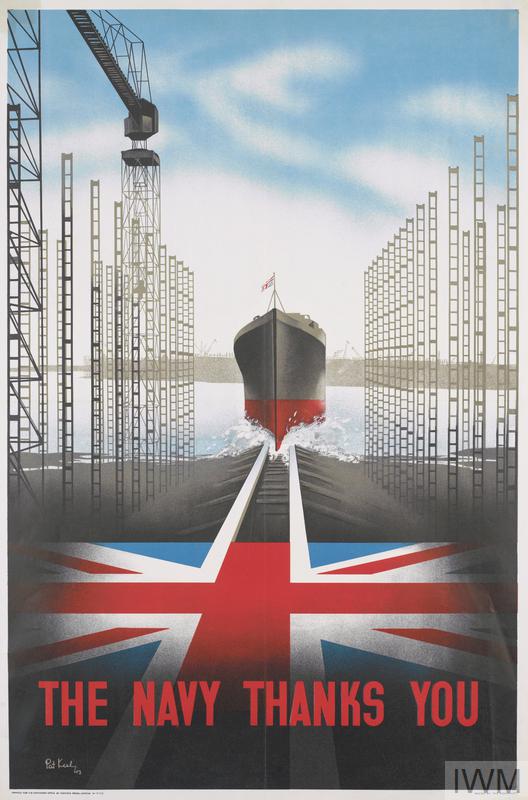

Since the early 19th century the Clyde region has been synonymous with shipbuilding and engineering. The work of men on the Clyde has been credited with shaping Glasgow’s industrial heritage yet little has been said about the women who worked in shipyards and on ships during wartime which surely contributed to the Clyde’s reputation!

It’s hard to get a sense of the individual experience of women working on the Clyde during the wars as working class women are not well-documented historically. Many Scottish women were, however, active in the engineering field throughout the wars and continued to pursue careers in industry after it. This heralded a new age in attitudes towards women in heavy industry and helped to pave the way for a better workplace for everyone!

Womanpower on the Clyde

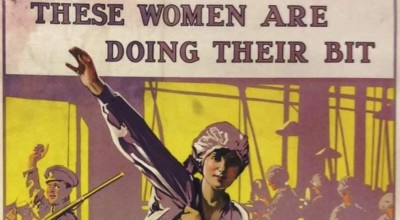

When conscription came about to draft all able-bodied men into the war, the women of Glasgow stepped in and began to take on traditionally male jobs which included work in heavy industry. There was great opposition to women being employed in industry from workers unions who opposed the government’s strategy of dilution, which was to replace skilled workers with un-skilled or minority persons such as women, older men or those with a physical disability. They argued that this would de-value the workforce and would only agree to allow these groups to work in industry if men who were at war were given job security. The Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act (1942) created an expectation that women should withdraw from industrial careers after the war as continuing to work was seen as taking a job from a man.

There were a very small number of women in shipbuilding and ship repair before the war, but these were mainly confined to work as French polishers, upholsterers and ship cleaners and were always paid less than men.[1] During the war, women worked in engineering workshops making parts for ships, building ships for the British navy and in administrative roles at company offices in the shipyard. One such woman was Mrs Agnes Smith, fifty year old mother of ten, who had previously worked in engineering workshops during WW1. When war broke out in 1939, she became the forewoman of a Greenock shipyard where she was in charge of 45 other woman working in shipbuilding being experienced in a lot of the jobs herself.

Despite having to work in an environment that was hostile to women workers their presence had unexpected benefits for the entire engineering workforce. Companies introduced new canteens for women workers where hot meals were served at all hours of the day, there was greater investment in leisure time activities, more regular break times and factories were forced to improve the quality of their toilet facilities.[2] By 1943, women comprised 35.4% of the labour force of the engineering industry[3] but still relatively few were involved in maritime engineering making up only 16% of the total workforce in this sector. In the same year, Churchill announced that the contribution of British women to the war effort had ‘definitely altered those social and sex barriers which years of convention had established.’[4] After the war, however, there still existed some long-held prejudices over what was viewed as work for men and what was work for women. This meant that most of the women who had worked in heavy industry during the war were forced to leave the workforce shortly after the men returned home. By 1947 58% of women employed in engineering during the war were made redundant although some 8 – 9,000 remained in shipbuilding and repair up to 1965.[5]

Clydeside was a particular target for air raids during WW2 as it was known for its shipbuilding works. After the war, many areas of the Clyde had been left devastated by bombings which along with the decreased demand for warships resulted in a sharp decline in industry. It is possible then to see women as just one of the groups of workers who suffered after the war as a decline in industry meant job losses as many of the great Clyde shipyards were closed down. The war had, however, emboldened women who now knew they had a place in the industrial workforce and were aware of the benefits of a career in maritime engineering.

Opportunities for the Industrial Woman

The role of women in shipbuilding and other engineering work brought many opportunities for the working class including a greater sense of camaraderie between women, economic freedom, increased social mobility and an awareness of the need for political action to improve the employability of women in industry. The census reports from 1931 and 1951 show that roughly 26% of the female population of the Clydeside were employed.[6] Not only were these women supporting the war effort, but they enjoyed a more distinct identity within the Scottish industrial workforce at this time.

The war was an unprecedented opportunity for women en masse to show the world that they had a place in heavy industry. Women excelled at their work in shipbuilding and repairing so much so that it gave impetus to political movements and charitable organisations who supported working-class women into a career in engineering. However, it wasn’t just during the war that Scottish women were having an impact on the maritime engineering scene.

From Scotland to the World

Being involved in maritime engineering was an excellent way to see the world in the 20th century, especially for a woman. The Woman Engineer Journal, published quarterly by the Women’s Engineering Society (WES), promoted with great fervour the training and apprenticeships open to women in engineering throughout Britain in the first half of the 20th century. Most of the members of the WES were politically active in campaigning for equal rights in the workplace for women and greater acceptance of their place in heavy industry. These women were aware of the need to fight against the gender bias within these job roles and celebrated women who were making an impact on the national and global scene through engineering work.

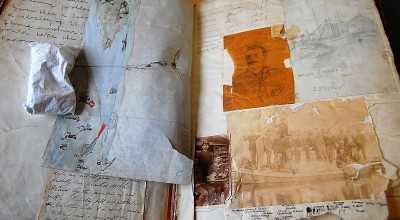

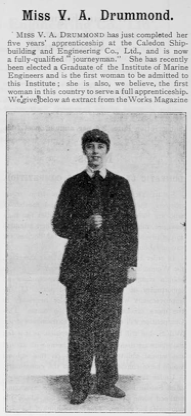

One such woman was Victoria Drummond MBE (14 Oct 1894 – 25 Dec 1978), who made 49 ocean-going voyages in her 40-year career circumnavigating the world on merchant ships as a Second Engineer. Eager to do what she could during the war she applied to the merchant navy although the war office refused to employ her directly as a naval officer telling her instead she was better off at home. Despite this, Victoria worked on cargo ships throughout the war and was awarded a medal for bravery after being subject to an aircraft attack at sea. She faced opposition from male engineers and female passengers who were derisive about her chosen career path. The Woman Engineer reported that her colleagues praised her for ‘sticking to what must have at times been a trying situation’ and that she was ‘well-known and respected’ on ship.[7] However, even the members of the WES thought Victoria was an unusual woman! A woman working as an engineer at sea was remarkably uncommon at this time, yet Victoria proved time and again that she could do the job as well as any man could and deserved her place as an engineer on board. Through her work she was able to travel around the world promoting the industriousness of women engineers although attitudes were slow to change and many women, including Victoria, continued to face prejudice in a male dominated career.

There were also women who had the benefit of studying for a degree at university in Scotland which enabled them to have more opportunities in the engineering world. Mary Thompson Irvine (1919 – 2001) was born in Partick and studied at the University of Strathclyde becoming the first woman in Scotland to become a chartered member of the Institution for Structural Engineers. Dorothy Rowntree (16 Jan 1903 – 5 Feb 1988) was the first woman in Britain to qualify in naval architecture graduating with a degree in engineering from the University of Glasgow. She worked in Fairfield Shipbuilding Yard and later moved to Beirut, Lebanon where she worked from 1928 at the American University there. Similarly, Ruth Pirret (1874 – 1939) was the first woman to graduate with a BSc in Chemistry from the University of Glasgow although she is known for her work contributing to the understanding of corrosion in marine boilers.. Whilst at University she won 8 prizes for her work and later moved to London to work on her research.

There were also women who had the benefit of studying for a degree at university in Scotland which enabled them to have more opportunities in the engineering world. Mary Thompson Irvine (1919 – 2001) was born in Partick and studied at the University of Strathclyde becoming the first woman in Scotland to become a chartered member of the Institution for Structural Engineers. Dorothy Rowntree (16 Jan 1903 – 5 Feb 1988) was the first woman in Britain to qualify in naval architecture graduating with a degree in engineering from the University of Glasgow. She worked in Fairfield Shipbuilding Yard and later moved to Beirut, Lebanon where she worked from 1928 at the American University there. Similarly, Ruth Pirret (1874 – 1939) was the first woman to graduate with a BSc in Chemistry from the University of Glasgow although she is known for her work contributing to the understanding of corrosion in marine boilers.. Whilst at University she won 8 prizes for her work and later moved to London to work on her research.

Another exceptional woman in Scottish engineering in the 20th century was Lady Margaret Moir (10 Jan 1864 – 5 Oct 1942), founder member and later president of the Women’s Engineering Society. She was born in Gorgie, Edinburgh and would later describe herself as ‘an engineer by marriage’ after marrying civil engineer Sir Edward Moir in 1887 and working closely on many projects with him such as the Forth Bridge, the Hudson River Tunnel and the Royal Albert Dock in London. Lady Moir travelled all over the world assisting her husband in dangerous engineering jobs such as the work on the Chinese railway and the Thames crossing. She was a staunch advocate for women’s working rights and believed in the importance of developments in industry to free women to pursue careers outside of the home. During the war she ran a relief scheme for working class women who did not have sufficient time off. Lady Moir and her associates worked weekends in factories instead of these women so that they could get some respite from their laborious jobs in industry. Like Victoria Drummond, Lady Moir did benefit from being a member of the upper class in society using the wealth and networks at her disposal to pursue a career path not open to many working class or poorer women. However, it was with the driving force of women such as these that greater opportunities were opened for women during the war and afterwards so that more might have the economic freedom and social mobility that an engineering career could bring.

Many of these examples of women engineers have been recognised by the WES and the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame[8] as exceptional persons who made an impact on the Scottish engineering workforce. As part of the Women’s Engineering Society’s centenary celebrations, a trail map[9] was made which highlights some of these Scottish women and their aptitude and perseverance in the field of engineering in the 20th century.

There is very little space given to women in the history of maritime engineering however, it is clear that their contribution to the engineering works and shipbuilding in Scotland throughout the wars and beyond should be included as a fundamental part of the Clyde’s history!

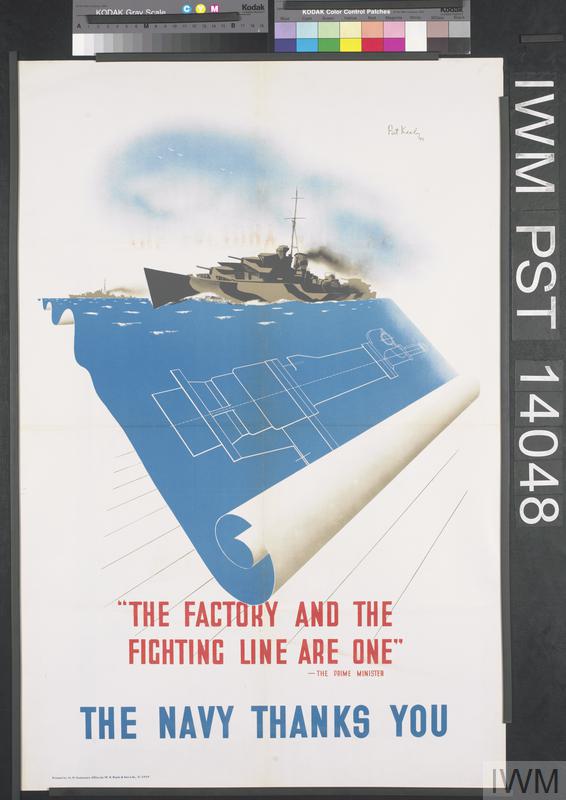

Images from top: Agnes Smith as a forewoman in uniform at a Greenock Shipyard. Credit: Imperial War Museum; Women were among those ‘thanked’ by the war office for their work in shipbuilding yet still faced much resistance in pursuing a career in engineering. Credit: Imperial War Museum; Announcement in The Woman Engineer Journal after Victoria Drummond completed her Second Engineer Certificate see Vol. 1. No. 9. 116.

[1] Murphy, H. 1999. ‘From the crinoline to the boilersuit’: Women workers in British shipbuilding during the Second World War. Contemporary British History. 13:4. P.85.

[2] Craig, M. 2011. When the Clyde Ran Red. Birlinn General. P. 97.

[3] Smith, H.L. 1984. The Womanpower Problem in Britain during the Second World War. The Historical Journal Vol. 27. No. 4. P. 929.

[4] Ibid. P.930.

[5] Murphy, H. Crinoline to the Boilersuit. 96.

[6] Chand, A. 2016. Masculinities on Clydeside. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 104 – 129.

[7] The Woman Engineer Journal Dec 1921, Vol. 11. No.9. 178/179.

[8] Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame (http://www.engineeringhalloffame.org)

[9] Women’s Engineering Institute Centenary Trail Map (https://www.wes.org.uk/centenary-map)